Kat KelleyGHTC

Kat Kelly is a senior program assistant at GHTC who supports GHTC's communications and member engagement activities.

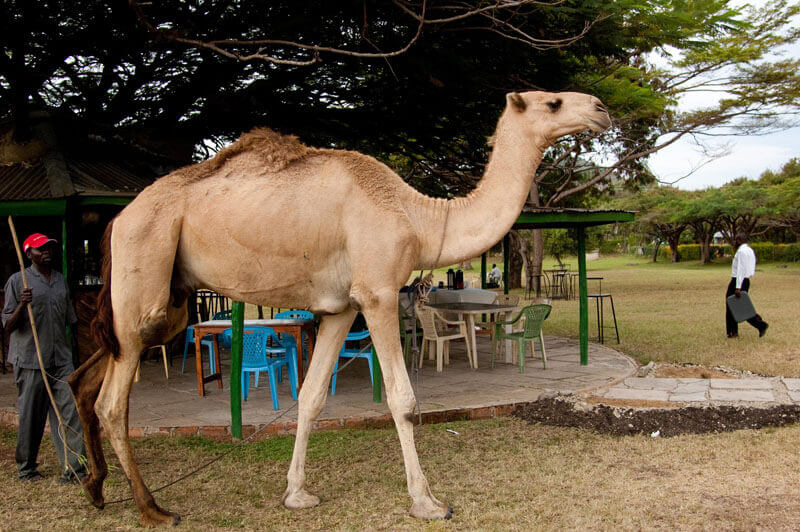

A new vaccine against Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) could save human lives by boosting immunity in camels. MERS, a virus that causes an innocuous cold in camels but kills nearly one-third of human patients, is primarily found in the Arabian Peninsula, where camels are common and 12 percent are infected at any given time. While the virus does spread between humans, camel-to-human transmission is believed to be a significant driver of new cases. Not only are camels an important host for the virus, but developing a vaccine for animals is cheaper, and the regulatory review is usually less burdensome than for a human vaccine. The vaccine uses a virus engineered to display the spike protein that defines MERS, prompting the immune system to create antibodies that will protect against MERS. The team vaccinated four camels and used an additional four camels as the control group. Three weeks after vaccination, all eight camels were exposed to the virus. While the camels in the control group all became infected, three of the four vaccinated were protected; it is unclear why the fourth was not.

Nature took an in-depth look at the development and testing of Ebola vaccine candidate rVSV-ZEBOV and how it could serve as a model for accelerating the research and development (R&D) of tools for other emerging threats. In less than two years, rVSV-ZEBOV went through multiple rounds of testing, culminating in a successful phase III clinical trial. In the typical timeline, it would take years to obtain regulatory approval for the trial, let alone to conduct it, and it would be performed in a setting with greater existing research capacity. The trial design was significant: the team enrolled nearly 4,000 individuals that were close personal contacts of Ebola patients, and those vaccinated were completely protected, while 16 percent of the control group became infected. By using patients’ contacts, they were able to identify and enroll at-risk individuals quickly. The researchers were also able to review preliminary results in real time, and after the vaccine proved to offer a significant advantage, the team immediately began to vaccinate all participants.

The White House released a National Action Plan for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) last week, with clear actions to be implemented by the US government over the next five years. The Plan is comprised of three goals: (1) Strengthen domestic capacity to combat MDR-TB; (2) Improve international capacity and collaboration to combat MDR-TB; and (3) Accelerate basic and applied Research and Development to combat MDR-TB. The first two goals call for increased diagnosis and treatment of MDR-TB patients while the third calls for R&D for new vaccines, drugs, and rapid diagnostics. Within the third goal, the plancalls for R&D of new products as well as research to improve the use of existing drugs; the development of strategies to identify the "most promising drug and vaccine candidates" within a given portfolio; and the identification of biomarkers (which are an early sign indicating whether a drug or vaccine will be successful) to accelerate clinical trials.

Scientists have genetically engineered male mosquitoes whose female offspring will be infertile in order to reduce the population of mosquitoes that transmit malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Normally, only half of an organism’s offspring inherit a non-dominant gene, however, the team used an approach called “gene drive” to ensure the trait—infertility—will be passed on at a rate of 90 percent. Gene drive involves using an endonuclease—a molecule that literally cuts DNA—to damage the original gene; the cell then duplicates the remaining, engineered gene, which results in two copies of the gene with the desired trait. While vector control is a cornerstone of existing malaria programs, there are concerns that this technique of drastically reducing the mosquito population could have unintended ecological consequences.