Kat KelleyGHTC

Kat Kelly is a senior program assistant at GHTC who supports GHTC's communications and member engagement activities.

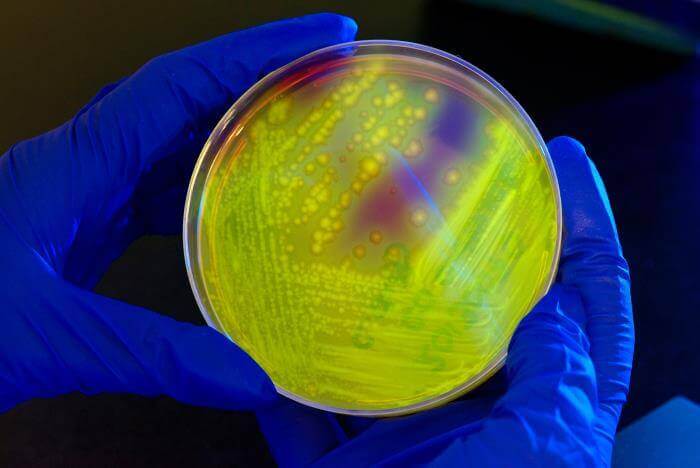

With the looming threat of a post-antibiotic era—in which minor infections are fatal due to growing drug resistance—world leaders are examining remedies for treating bacterial infections from the pre-antibiotic era. One such treatment, known as phage therapy, uses live viruses that attack bacteria and ignore human cells. The method, which was discovered in the early twentieth century, was largely abandoned after the discovery of penicillin and is currently only in use in Russia, Georgia, and Poland. Nearly a century later, the European Commission is funding a US$4.2 million clinical trial to test phage therapy on 220 patients in France, Belgium, and Switzerland. The study will use a cocktail of these viruses—known as bacteriophages—developed by French company Pherecydes Pharma. Phage therapy is expected to be an option of last resort to treat infections that are resistant to three or four drugs.

American pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson will initiate clinical trials of an experimental HIV vaccine that completely prevented HIV infection in half of the monkeys that received the shot. Vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys were exposed to simian immunodeficiency virus—a relative of HIV—on six occasions, after which all of the unvaccinated monkeys were infected. The clinical trial will include 400 healthy volunteers from the United States, East Africa, South Africa, and Thailand. If the vaccine appears to be safe and effective, Johnson & Johnson plans to commence phase 2b trials within the next two years.

Each year, a new flu vaccine is developed to protect against the three to four strains of the influenza virus that are expected to be most virulent. The vaccine is comprised of antibodies—proteins developed by the immune system—against those selected strains. However, new research out of Rockefeller University could pave the way for the development of a universal flu vaccine that would provide lifetime protection against all strains of human influenza. The team at Rockefeller noticed that humans naturally develop sialylated antibodies—antibodies with sialic acid at one end—after receiving a seasonal flu vaccine, specifically the H1N1 vaccine. The team then vaccinated mice with either the standard H1N1 vaccine or an experimental vaccine that included sialyated antibodies against H1N1. The two vaccines provided equal protection from H1N1, however, only the vaccine containing sialyated antibodies provided protection against other strains of H1 influenza. In the lab, the researchers determined that the sialic acid allows antibodies to attach to human immune cells as well as the virus, and consequently coordinate the human immune response by prompting the production of broadly protective antibodies, rather than antibodies specific to one strain of the virus.

The US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit—one of 12 regional courts in the United States that reviews decisions made by local, district courts—upheld a district court’s decision against “product hopping,” a mechanism by which brand name pharmaceutical companies prevent competition from generic manufacturers by slightly adapting a product and removing the original from the market. In this case, pharmaceutical company Actavis had altered Nameda, a drug for Alzheimer's disease, and planned to remove the original version from the market, claiming that the new version is superior. However, the court ruled in People of the State of New York v. Actavis PLC that such action would be “unlawfully anticompetitive” and would violate the US Sherman Anti-Trust Act. The exclusivity period of the original version of Nameda was set to expire in July 2015, after which time generic versions of the drug could enter the market, while the exclusivity period of the new version would not expire until 2029. The court’s decision states that Actavis’ motivation for removing the original version from the market was to inhibit sales of generic versions of the original formulation of Nameda, as automatic substitution laws allow pharmacists to provide a generic version when a brand name drug is prescribed.